The Lever Action is America’s Rifle

America's Unique Contribution To International Firearms Design

When the Chinese invented gunpowder in the 9th Century, it was a big deal. Much flash, big bangs, and a super-cool new way of celebrating the New Year. Those were good enough for the next three hundred years or so, but eventually somebody got to wondering what else the stuff could be used for, and by the 12th Century the first crude “guns” were emerging, in the form of hollow tubes of various sizes closed at one end, open at the other for cramming in a basic mix of sulfur, charcoal, and saltpeter behind stones, iron balls, scrap metal, and/or anything else the experimenter felt like throwing out the muzzle, and using a touchhole to introduce a spark, flame, or fuse.

When the Chinese invented gunpowder in the 9th Century, it was a big deal. Much flash, big bangs, and a super-cool new way of celebrating the New Year. Those were good enough for the next three hundred years or so, but eventually somebody got to wondering what else the stuff could be used for, and by the 12th Century the first crude “guns” were emerging, in the form of hollow tubes of various sizes closed at one end, open at the other for cramming in a basic mix of sulfur, charcoal, and saltpeter behind stones, iron balls, scrap metal, and/or anything else the experimenter felt like throwing out the muzzle, and using a touchhole to introduce a spark, flame, or fuse.

Just as likely to explode and destroy the user as the target, the science of gunpowder and projectiles slowly progressed till it was a regular fixture for field artillery and naval applications by the 1600s, and in that time frame more sophisticated methods of igniting gunpowder, combined with the growth of industrial capability and more portable and dependable personal-carry long guns and pistols, all began to accelerate.

Skilled craftsmen produced smaller tubes a man could actually shoulder or carry on a belt, and the ignition process ran through a technological evolution from matchlock to wheellock to snaplock to flintlock to caplock to self-contained metallic cartridges, all in relatively quick succession (as the turtle travels, anyway). Barrels incorporated rifling, sights were developed and refined, gunpowder itself was improved and diversified for specific uses, and the world of personal combat on the battlefield and success in the hunting camp was transformed forever.

Along the way, as with anything that works well enough to become a centuries-old institution, there were milestone standouts. The European matchlock of the15th Century was arguably the great-great-grandpappy of today’s modern rifle, with the first practical (mostly) on-board ignition system. It allowed the gunner to keep both hands on his weapon, both eyes on his target, his muzzle from wobbling all over while touching a loose “match” (actually a smoldering piece of rope) to the flash hole, and (once lit) that match was attached to the simple lockwork and didn’t have to be carried separately or dropped and lost during the heat of battle.

German matchlock musket with serpentine lock – The Museums, Schloss Glatt

The flintlock, attributed to the French in the 17th Century, is probably one of the most famous early designs known widely to gunnies today. It was simple, reliable, easily serviced, long-lived, flints were widely available and quickly replaced by the user in the field, and later versions incorporating those new-fangled lands and grooves were quite effective in the hands of colonial soldiers delivering a very clear “Thanks For Visiting, But It’s Time To Go Home Now” message to the Redcoats at Lexington and Concord in 1775.

Flintlock pistol detail – Palace Armoury Valletta

Skipping forward, other nations have produced stand-out classics that live on in history books, private collections, museums, and still in actual use today, decades after they were introduced. In comparatively modern times, Germany gave us Peter Paul Mauser’s enduring bolt-action 1898 rifle, Georg Luger’s pioneering 1902 semi-auto pistol, and Walther’s ground-breaking double-action P38 pistol; Italy’s 400-year-old Beretta firm generated the current US military M9 pistol; Great Britain produced the much-respected and long-running Enfield .303 bolt-action battle rifles, along with their distinctive Webley break-top double-action military revolvers; Russia built millions of the brick-solid Mosin Nagant bolt-action military rifles and Nagant double-action revolvers; and Austria originated the Glock pistols in 60% of our law enforcement leather. There are other historically important designs like the Swiss straight-pull Schmidt-Rubin rifle, the French Lebel’s tube-magazine bolt-action, and the Japanese Nambu pistol, all of which have their place in the Gun Designer’s Hall Of Fame, but certain models are just inherently more recognizable than others, and whether that’s due to a good design or a great press rep, the result is the same. Hold up a Luger or a Webley in front of a dozen even halfway gun-savvy people, and you’ll get a dozen nods of recognition.

Mosin-Nagant Infantry Rifle Model 1891, Russia. Caliber 7.62x54mmR. From the collections of Armémuseum (Swedish Army Museum), Stockholm, Sweden.

And, the US has earned our own place on the worldwide stage.

Where Everybody Knows Your Name

Three places, actually, with three enduring designs that have stood the test of time in a world where the latest and greatest runs heavily to plastic and hi-cap. All three, with roots that date back well over a hundred years, are still in production by both their original makers and by other companies with their own variations, and still selling well to a market segment that appreciates the history, the tradition, the spirit, and the enduring utility of what they represent and offer.

The first handgun was not invented in America, but Colt’s 1873 Peacemaker certainly was, and with 143 years of backstory behind it that include tales of adventure and exploration here on our shores and on far-away continents abroad, there’s probably no better-known handgun around the globe that crosses borders, boundaries, and cultures, than the famed “cowboy” gun so widely carried in the glory days of the Old West, and so immortalized by the silver screen since The Great Train Robbery in 1903. Still produced by Colt, and widely copied by various foreign makers, the Single Action Army figures prominently on anybody’s list of the Ten All-Time Most Significant Handguns In Firearms Development.

Volcanic repeater mechanism, here as a pistol. Edited from the file Volcanic by Homo.

Equally, the first auto-pistol was not an American design, but in 1911 Colt’s new .45 ACP pistol developed for potential military contracts, from the mind of the most prolific firearms designer who ever lived, John Browning, was the first truly practical big-bore self-loading magazine repeater that offered power, reliability, and rugged durability in a package that was arguably one of the best issued sidearms of its day, and remained in service with our military branches until it was officially phased out in favor of the 9mm Beretta M9 pistol in the late 1980s. Also still made by Colt, and also manufactured by dozens of other companies here and abroad, the 1911 rides on in civilian holsters for concealed carry defense, shows up regularly at weekend ranges and in competition, supports a number of specialized shops as a base gun for full-blown custom projects, and is more popular today than at any other time in its previous 105-year history.

Mauser M98 Rifle from the collection of Vaarok, photograph released for the public good. A Gewehr 1898 produced by “Deutsche Waffen und Munitionsfabriken” in 1905, with a regimental stock tag indicating issue to the 114th Badisches Infanterie Regiment. Pictured with a five-round stripper clip of 8x57IS standard ammunition, and a SS98/05 “butcher blade” type bayonet, which is regrettably missing the grip panels.

And, last, but far from least, the purely 100% American lever-action rifle, originating in concept with Horace Smith and Daniel B. Wesson and their early attempts to create a repeating handgun with self-contained “cartridges” in the 1854 Smith & Wesson Lever Pistol. Further development led to Oliver Winchester’s involvement, and when Smith and Wesson finally gave up on the lever-action idea because existing ammunition technology was still lagging too far behind and turned to the revolver, Winchester parlayed the under-barrel tube magazine and reciprocating lever-actuated bolt repeating rifle concept into the foundation of a firearms empire with a name that became as well-known as Colt in the industry. Winchester owed that empire largely to Benjamin Tyler Henry, who both advanced rimfire ammunition to practical levels and the primitive lever-action itself to make a functional rifle that could use it. The result was the 1860 Henry, and one of the first successful long gun repeaters. At the time, its only real competition was the relatively short-lived Spencer that also saw use in the Civil War, but the Spencer design was quite different in operation and only lasted from 1860-1869. The 1860 Henry spawned the 1866 and 1873 Winchesters based on the same action, and the basic configuration of a lever-operated repeating rifle lives on with two domestic makers and a handful of foreign manufacturers selling to the US under various branding.

Early Days

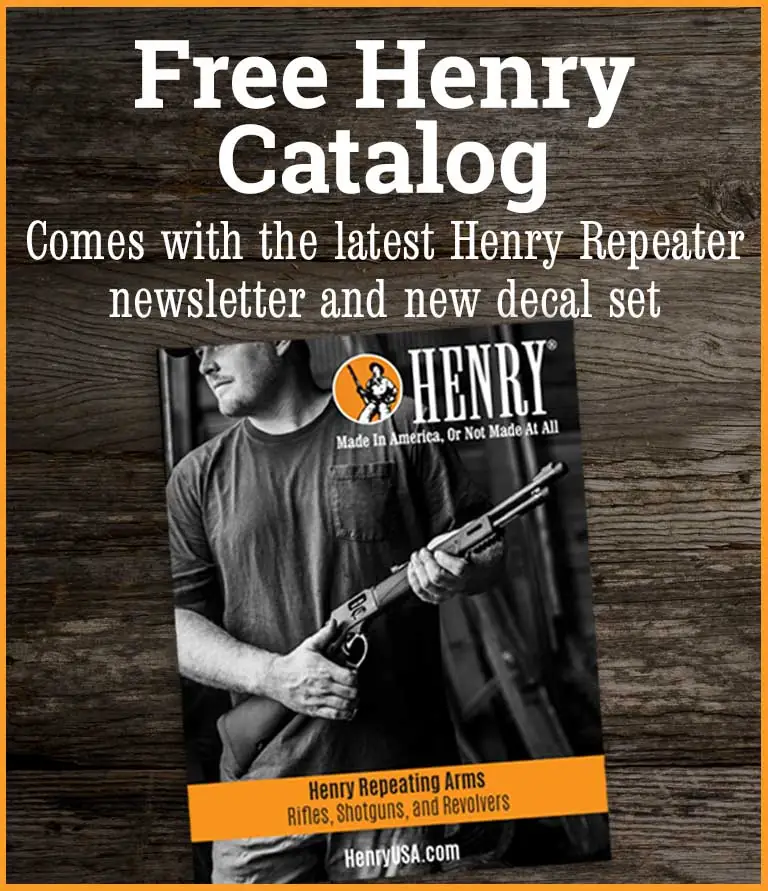

Mod 60 Henry rifle, magazine open for loading; 3 Henry rounds, one round 44-40 to compare

Of the two early patterns, the Henry and the Spencer, the Henry’s attached underbarrel magazine system was much simpler to use than the Spencer’s 7-round magazine located inside the buttstock. Spencer shooters had a more complicated action and magazine to deal with, where a spring tube providing forward pressure had to be pulled out the back of the stock, rounds slid in with the muzzle down, the spring tube replaced, the lever cycled to chamber a round, and the hammer cocked independent of the lever. Each time the lever was cycled for ejection and feeding, the hammer had to be cocked manually. The Spencer’s primary weakness was a very “lose-able” magazine spring tube that had to be completely removed from the gun for loading, aggravated by the relatively slow shooting process. Its primary advantage over the Henry was a more powerful rimfire round, with a larger-caliber bullet.

Henry shooters, with over twice the Spencer’s payload in the Henry’s 16-round magazine, slid the follower fully forward in its open channel cut to allow the muzzle collar to rotate out of the way for loading by inserting rounds into the magazine’s open end (muzzle up here), swiveled the collar back in line, let the follower drop to provide backward pressure, and cycled the lever to feed, cock, and extract/eject. The Henry’s primary weakness was the open follower slit along the magazine tube that tended to pick up battlefield gunk and grit, and also prohibited a practical wooden fore-end to avoid charring hands during long strings of fire. Magazine-wise, its primary construction advantage over the Spencer was that there was nothing that had to detach from the rifle to load it, and no part that could be lost to render it into a single-shot.

The reasons why the Henry succeeded and the Spencer didn’t could be argued, but today the Henry’s overall superiority is obvious, and once Nelson King brainstormed the side loading port and entirely enclosed magazine for Winchester in the 1866 Winchester (AKA Improved Henry) model, the levergun was off and running.

While the sun was setting on paper cartridges and percussion caps with all of their weaknesses, and rising on the development of self-contained metallic cartridges with all of their benefits, dependable repeaters to use that new ammunition technology were quickly demanding attention among those who immediately got the basic mathematical equation of More Rounds On Board= More Shooting Time/ Less Loading Time+ Increased Save-My-Life Odds, both on the battlefield and on their own during the violent expansion of an often hostile Westward Ho exploration and settlement.

In uniform, one man with a Henry repeater could put out the same volume of aimed fire in one minute that an entire infantry squad could with 1863 Springfield rifles. A hunter, prospector, homesteader, peace officer, or cattle rancher had infinitely better chances of bringing home the bacon, fending off marauders of all sorts, and backing down belligerent owlhoots, with a long gun that held one up the spout ready to go, backed by up to 15 more right in line and ready for action.

America’s Rifle

While our country was only a hundred years old, and still expanding, gun ownership across the pond in Europe was largely restricted to either military or gentry. Military use was…military use. Ownership outside the military was more a matter of wealthy land owners hunting on long-owned private lands, in settled circumstances and established (known) areas. Self-defense was not a priority, and the idea of regular everyday people hunting with firearms for either sport or subsistence took a while to develop.

Here, from 1850 to 1900, times and places west of the Ol’ Mississippi were still unsettled, lands were wide open, new territory needed exploring, law enforcement was not a 911 call away, and those who lived or ventured far from the dusty streets of civilization depended on themselves and reliable tools for their daily existence.

The lever-action evolved steadily during the last half of the 19th Century from the relatively anemic .44 Henry Rimfire into more powerful centerfire rounds like the .44-40 Winchester, and on through the immensely popular Model 1894 .30-30 Winchester into the mighty Model 1895 Winchester with its .30-06 Government chambering carried by the Texas Rangers and the .405 Winchester version that Teddy Roosevelt affectionately referred to as his “big medicine” for lions in Africa. During those years, the levergun was king among those who needed or preferred a trim, easy carrying, reliable repeater for everything from squirrels to moose.

Even when the century that spawned it ended, the lever-action continued to rule in civilian hands in America, till the bolt-action spillover from our Army and World War One picked up momentum, first with the Norwegian-based 1898 Krag service rifle, and later with the German-based 1903 Springfield. Although generally outclassed in power and range, Winchesters, Marlins, and Savages kept right on going in the woods, the trucks, and the saddle scabbards, side-by-side with commercial bolt-action versions as they adapted for civilian consumption, well into the 1950s. Along the way, the unique “hammerless” Savage dropped out of sight, Marlin soldiered on, Browning entered the field with thoroughly modern interpretations built overseas, Winchester ceased domestic production and moved its levergun line-up to Japan, Italian makers geared up to export thousands of Winchester lever-action replicas to the US, Ruger tried a foray into levergun-land that didn’t pan out, and a small company in Brooklyn, of all places, started up lever-action production of a humble budget-entry .22 rimfire.

Today

Where is America’s rifle today?

Alive and well, thanks, although the market and the players have changed considerably. Much as we die-hard levergunners might prefer otherwise, the truth of the matter is quite obvious – the bolt-action has taken over the bulk of the hunting market, along with the long-range market. Progress was inevitable; the bolt-gun is simply more efficient in the broad picture when it comes to strength, range, accuracy, and range/accuracy enhancers like optics, after market triggers, and stock bedding.

While the Italian repros are still doing well for traditionalists, and the Brownings are well-respected as modern designs, the Winchesters are now comparatively limited in numbers and high-dollar imports with modified actions incorporating modern safety features, and the results of the Marlin buy-out by Remington in 2007 and subsequent move to the Remington plant in New York left the Marlin brand in turmoil, with severe quality control issues and the suspension of certain lever-action models that the company is still recovering from.

Enter that little Brooklyn outfit, although it’s no longer a “little” outfit. With Marlin and Henry being the only domestic levergun manufacturers left, and Marlin down to a handful of models, if you’re on the prowl for a brand new made-in-America version of the time-honored pattern it’s between those two brands, and Henry offers by far the biggest selection in models and calibers. The little entry-level H001 in .22 LR/L/S that started it all in 1996 is still produced, although the Henry operation is now split between Bayonne, New Jersey, and Rice Lake, Wisconsin, and that model led to variations that include Henry’s flagship Golden Boy, Frontier, Small Game Rifle, Golden Boy Silver, Evil Roy, Silver Eagle, engraved special tribute editions, and short (but street-legal) Mare’s Leg pistol versions, all in the rimfire calibers from .22 Short through .22 Magnum to .17HMR that built Henry’s rep as “The Smoothest Gun In The West”.

With the rimfires doing so well, Henry brought out their first centerfire model, the .44 Magnum Big Boy, in 2001 in a hardened brass alloy frame followed by the .357 Magnum and .45 Colt, and those led over the years to successive handgun-calibered models in steel frames, the introduction of the .30-30 Winchester and .45-70 Government calibers in brass and steel frames, an All-Weather series, the Color Case Hardened Model, and both brass and steel engraved Wildlife tribute models. Not to mention the centerfire Mare’s Legs in .357 Magnum, .44 Magnum, and .45 Colt, or the first-class instant-retro-collector pieces like the Henry Original Rifle (1860 edition in .44-40) in both brass (alloy) and iron (steel) frames. Or deluxe limited-edition engraved One Of 1000 Editions. Or the 2016 total departure for Henry – the introduction of the Long Range Lever Action in .223 Remington, .243 Winchester, and .308 Winchester; with thoroughly modern gear-driven lever action, strong rotary-bolt-head-lockup, light-weight hard-anodized aluminum receiver, detachable steel box magazine, sling swivels, tapered sportier barrel, checkered walnut, solid rubber recoil pad, and drilled & tapped for optic sights.

Altogether, Henry currently produces 8 different lever-action models, from handgun to carbine to rifle configuration, in 13 different calibers, from basic plinker to deluxe collector, and in a wide range of finishes and options to please anybody from first-gun beginner to old-hand hunter. The current levergun market ain’t what it used to was, but America’s rifle still stands proud, and you’re missing out if you’re not a part of it.